Elizabeth Hosier (with contributions from the volunteers working on the project)

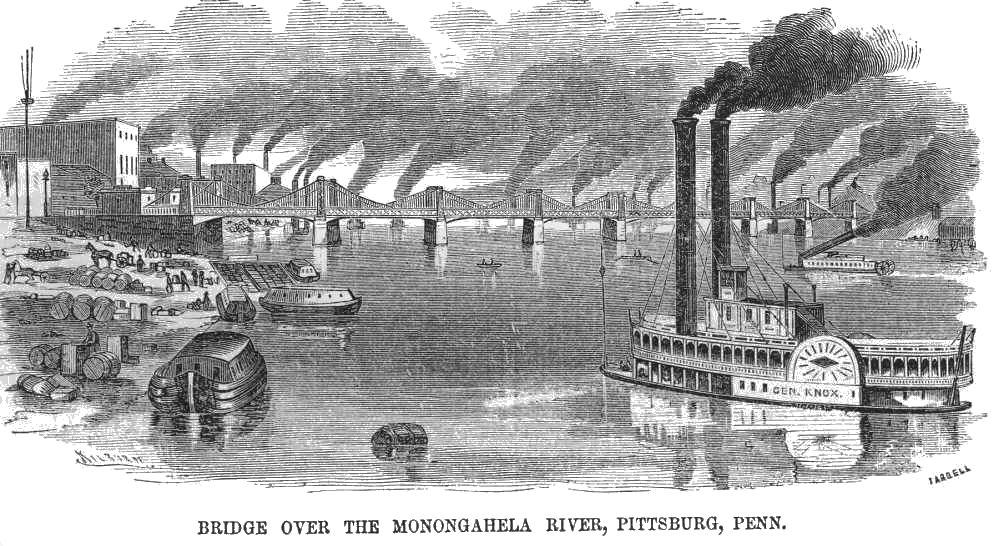

Pittsburgh earned the nickname “the Steel City” in the late 1800s as entrepreneurs like Andrew Carnegie established steel mills around the city. In fact, Carnegie Steel’s contributions to the industry advanced it by leaps and bounds throughout the 1880s. As the steel industry grew, the city did too and by World War Two, the demand for steel meant the mills were running 24 hours a day. Pittsburgh produced 95 million tons of steel for the war effort. This also led to massive amounts of pollution and a visitor to Pittsburgh claimed “Pittsburgh, without exception, is the blackest place I ever saw…” After the war, the city made efforts to clean itself up with initiatives for clean air and clean rivers. Throughout the 20th century, the city improved environmentally and culturally, developing into the 90 unique neighborhoods that make up the area now.

U.S. Steel production peaked in the mid-1970s and Pittsburgh remained a thriving industrial giant. However, foreign steel production led to a collapse of the U.S. steel industry in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s. This led to the closure of mills and massive loss of jobs for people in the Pittsburgh region. In fact, the unemployment rate in the region peaked at 17.1% in January 1983. Pittsburghers were left to struggle to make ends meet as the economic recession hit them hard.

Today, not all Pittsburghers are die-hard fans, but unlike other cities, even non-fans in the region seem to know how the Steelers are doing. For a long time the Steelers meant more to the region than just being a football team and that stems from the economic downturn of the 1970’s and 80’s.

The Steelers franchise was founded in 1933 by Art Rooney. Originally named the Pittsburgh Pirates, the team seemed to be great at one thing, losing. By 1940, they had changed their name to the Steelers just in time for WW2 to cause a player shortage. They spent a season as the Phil-Pitt Steagles and another as the Chi-Pitt Carpets. After the war, they showed some improvement, making the playoffs for the first time in 1947, they lost their first round game and never made another until after the AFL-NFL merger in 1970. In fact, hiring Chuck Noll in 1969 and the merger seemed to have changed the team’s luck completely. Knoll had an eye for talent and drafted some of the most notable names in Steelers history. They became a dynasty going to the playoffs eight times and winning four Super Bowls in six years. The team earned the nickname “the Super Steelers” and their sudden winning streak was exactly what the struggling region and its people needed.

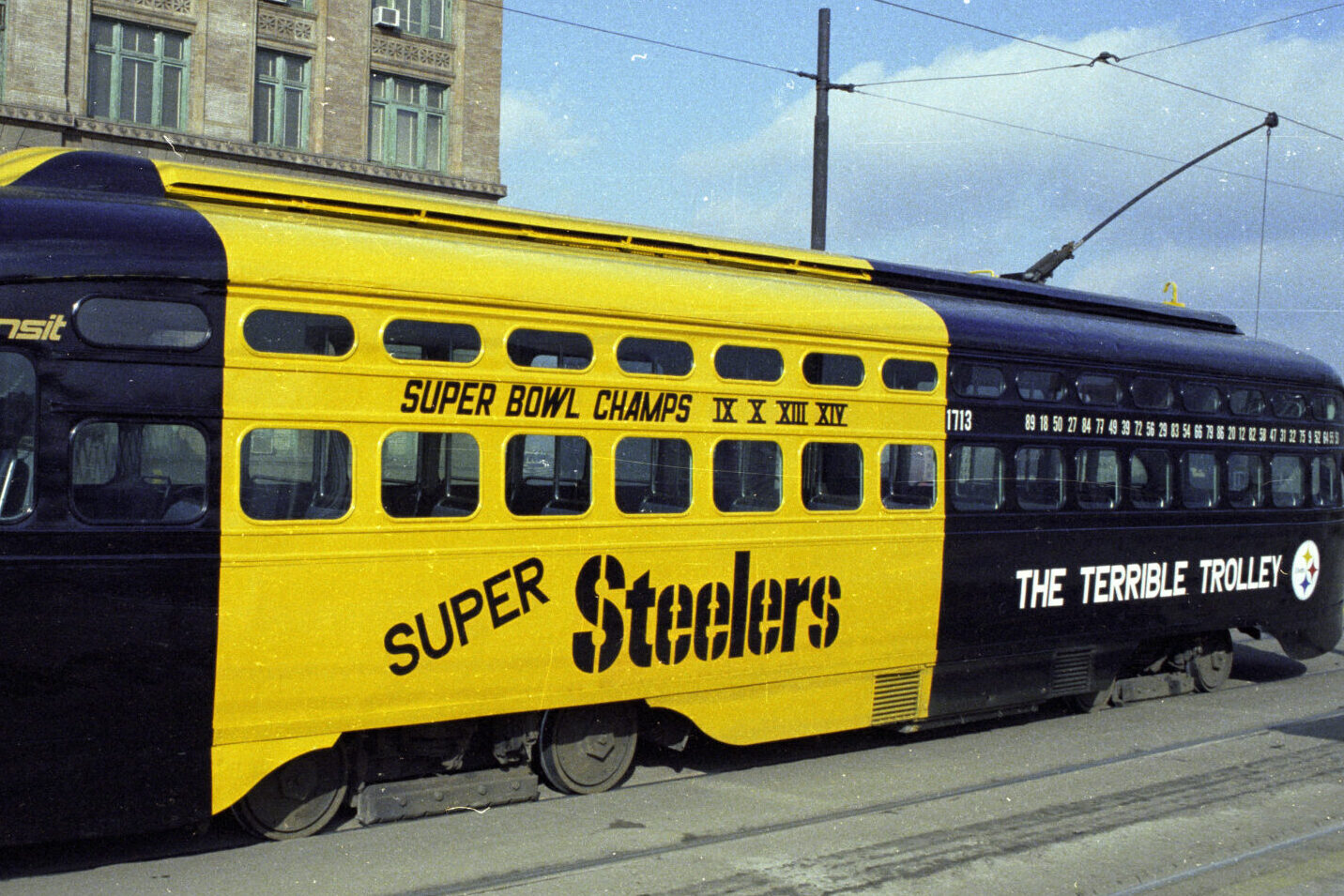

The city came alive as they watched their team. Myron Cope, former Steelers radio announcer, started the iconic Terrible Towel tradition. The yellow rally towel with black letters debuted on December 27, 1975 and was an instant classic. In fact, the idea took hold in several aspects and everything in the city became “terrible”. Steelers fans have taken photos with their towels all over the world and even in space!

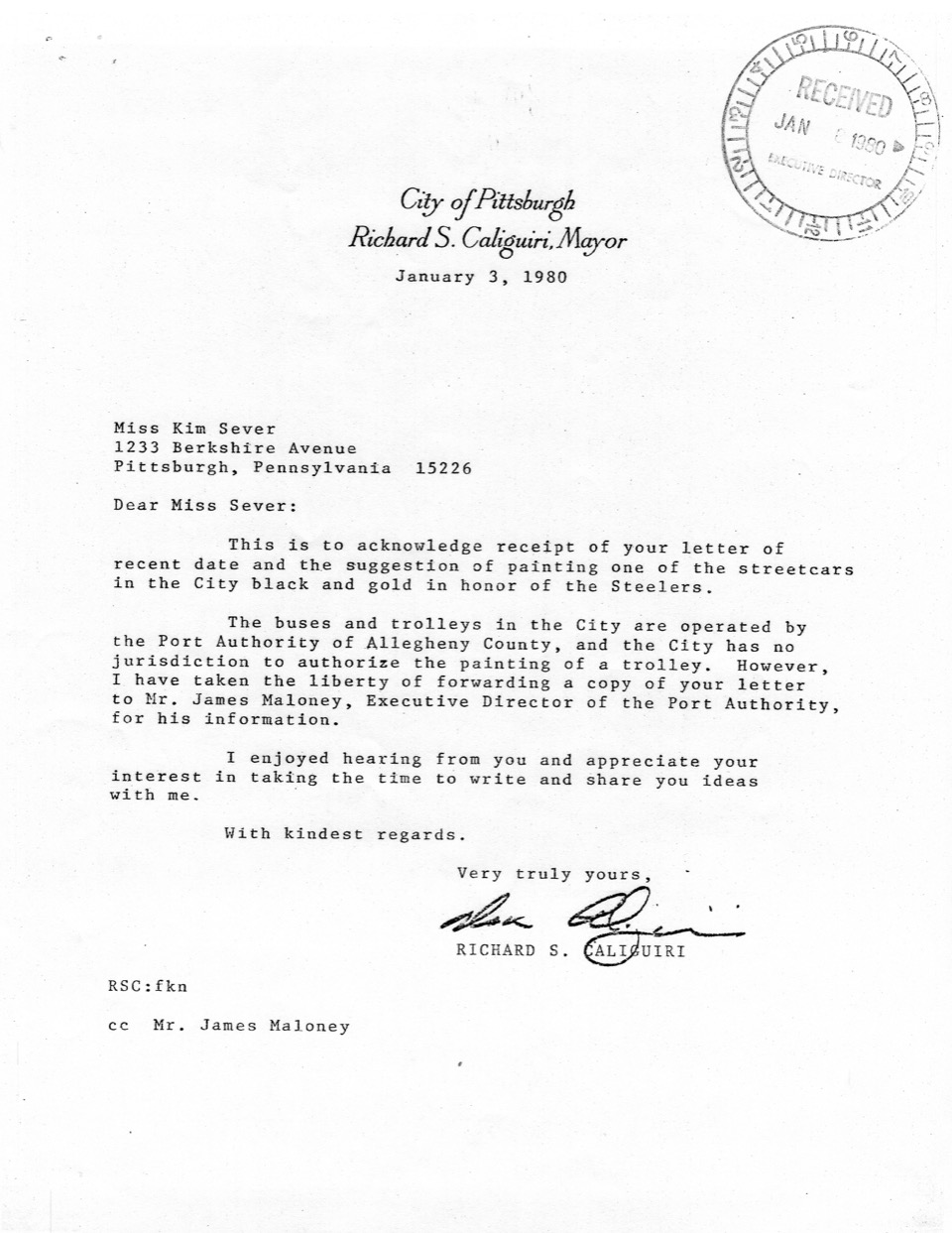

Everyone that was around when the Steelers became super has a story about watching those games, gaining hope with each first down. Someone who remembers those Steelers is Kim Sever. Kim grew up surrounded by adults in Pittsburgh – watching football and helping cook dinner. She spent time with her grandmother and learned a myriad of useful life-skills, including the art of letter writing. It was during one of those Steelers games that Kim got the idea that the city should have a trolley that was painted to honor the team and the “terrible” tradition. Her grandmother suggested that she write a letter with the recommendation. Nine-year old Kim sat down and wrote to Mayor Richard Caliguiri. The mayor wrote back explaining that he wasn’t in charge of the public transit system but that he would pass along her suggestions

![Letter written by a 9 year old that says "MR. City Promoter, My Name is Kim Sever, I am 9 years old and I had this idea that mabye [her spelling error] the city could have a trolley painted black + gold that says terrible trolley. If the city doesn't have the money for a new trolley you could just paint one of the old trolleys black + Gold OK? Sincerely, Kim Sever"](https://pa-trolley.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Kim-Sever-Letter-e1687275187587.jpeg)

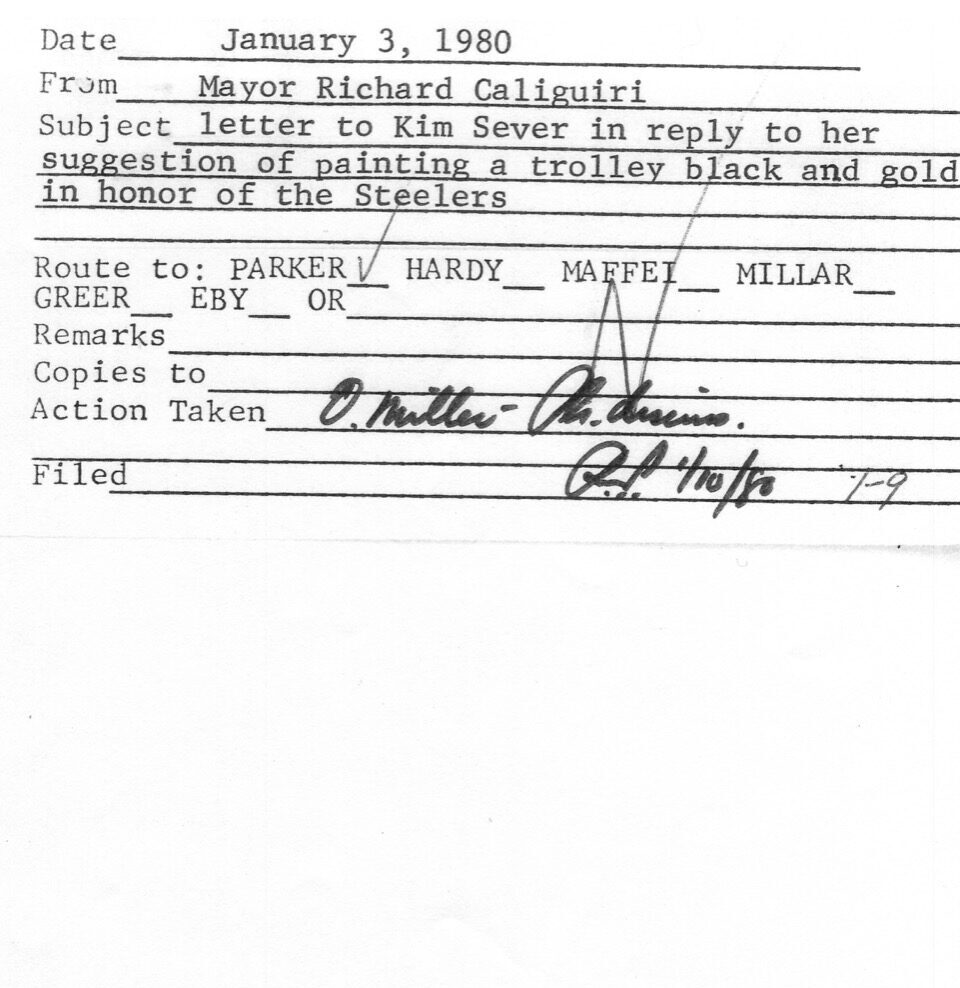

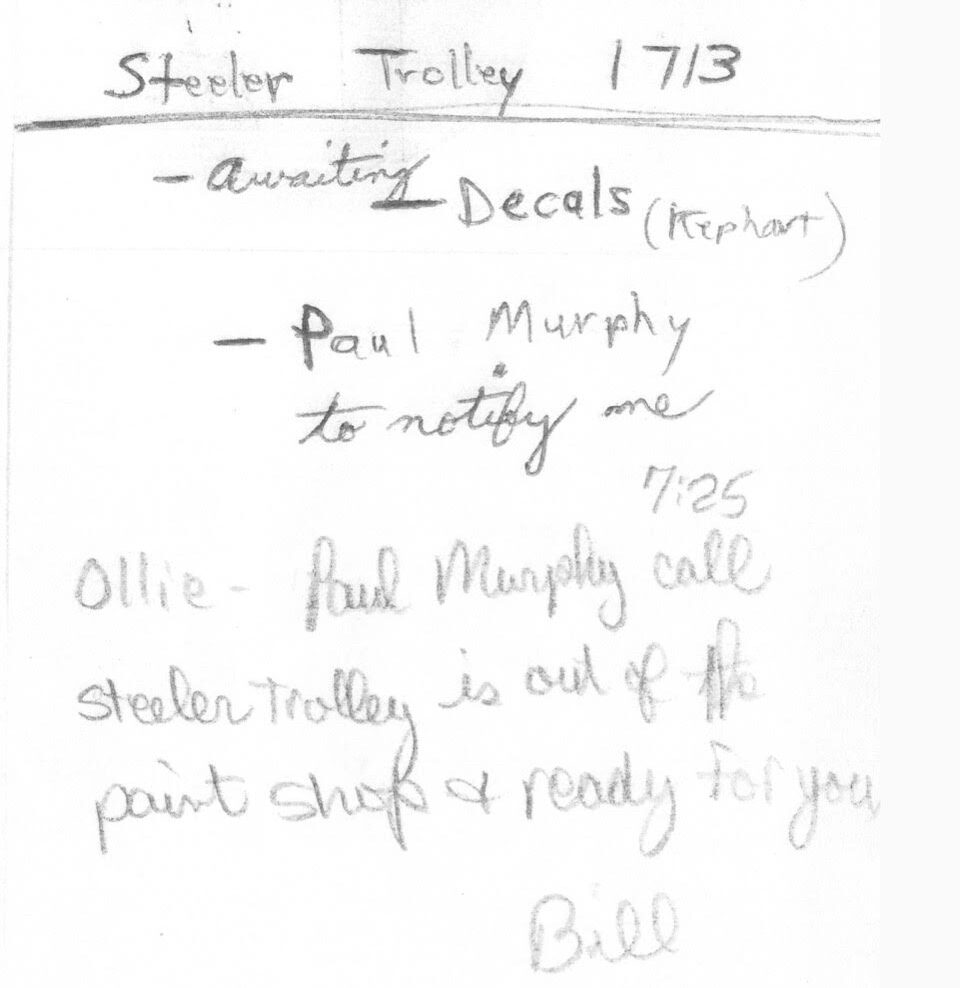

Mayor Caliguiri’s response and memo to the Port Authority of Allegheny County (now Pittsburgh Regional Transit or PRT) was dated January 3, 1980. On Port Authority’s internal memo about the letter, they indicate that they took action to move forward with the project by January 10, 1980. In just one week, they were working to paint a car in the suggested theme. Lastly, we have a handwritten note saying the car had been painted and was awaiting decals, while that note is not dated, we do know that the Terrible Trolley began running the streets within just a few weeks of the mayor’s letter.

The car that was chosen for the paint job was PAT PCC 1713. It was built in 1949 by the St. Louis Car Company and originally ran along the Charleroi and Washington interurban lines. The car ran as the Terrible Trolley throughout most of the 1980s. It was retired in 1988 but returned to service only a year later. It was finally retired for good in 1998. Port Authority then sold several of their retired cars to different entities, including some private collectors. PAT PCC 1713 was one of the cars sold into private ownership. The car was stored indoors in Ohio for the past 25 years. The owner did some repairs to it but overall did not have the time or resources to complete a restoration and made the decision to sell it to the Museum. Brownlee Trucking, Inc. agreed to help transport the car from Ohio to the Museum. In addition, the Museum was able to secure an NFL license agreement through the Pittsburgh Steelers and the Eamon Foundation, the charity designated by Myron Cope’s estate as the owner and beneficiary of “The Terrible Towel” trademark.

We have already begun to restore 1713. The project to return it to the Terrible Trolley paint scheme and to make it operable is one of our youth volunteer projects. We are pleased to announce the co-project managers are Jack Jost, who is only 17, and Ayden Kendlick, who is 18. They are being advised by more senior volunteers and staff, but they are taking control of the project and they have already made some great progress. The first step was to pressure wash and clean the car inside and out. This process was quite the endeavor as the car had been untouched for quite some time and a few critters had made their way inside. Next, they worked quickly to rewire the interior lights and make sure they worked properly. Both of these steps happened within just a week of 1713 being at the Museum.

Since then, the work has continued to move quickly. The volunteers worked to jack the car up off the group and remove the trucks (the structure that contains the axles and wheels) for inspection and repair. They have also removed the motor-generator (MG). The crew has been inspecting the rust caused by salt damage from the years spent driving in Pittsburgh’s winters, a good portion of this underbody steel will need to be replaced. They have also met with Prime Collision to discuss the painting process and timeline. While inspecting the paint, volunteers came across areas where they could see the layers of past paint jobs, including paint from when it was the Terrible Trolley. Additionally, when re-painted, Port Authority did not remove all of the decals leaving spots where the faint outlines of players numbers are visible in the right lighting.

As we make progress on this car, we plan to continue to update our blog – click the “Terrible Trolley” tag below to see all the latest news!