Milton Hershey’s Streetcar System

Written by George Gula

Edited by Kristen Fredriksen

February 12, 2021

It wasn’t until Milton Hershey was in his forties that the chocolatier introduced milk to his chocolate and made a fortune, becoming one of the richest men in America. He was unusual for his time as he used his wealth to help others. Milton Hershey built a town with “practically every conceivable public convenience” including a state-of-the-art streetcar system to transport his workers and a steady supply of fresh milk from local farms to the Hershey Chocolate Factory (Brill Magazine, Vol. 10 No. 6, 1916).

Hershey was born in Derry Township, Pa. on September 13, 1857. Noting that he never did well in school, Hershey’s father apprenticed him to a printer after he finished fourth grade. The young boy did not like the job and was soon fired. His mother then arranged to obtain a job for him with a confectioner in Lancaster, Pa., a job which he very much enjoyed. At the age of 19, Milton Hershey opened his own candy business in Philadelphia in 1876, hoping to profit from the Centennial Exposition opening in that city. He kept this business going for 6 years, but had to close it in 1882. He then moved to Denver where he got a job as a candy maker, learned to make caramels with fresh milk, and soon opened his own candy businesses first in Chicago and then in New York City. In 1883, he moved back to Lancaster where he opened the Lancaster Caramel Company, and that business became a success.

In 1893, Hershey attended the Chicago World’s Fair where he saw a German exhibitor demonstrating chocolate-making machinery. He was so impressed that he purchased the machinery and began making chocolate-covered caramel at his Lancaster plant.

Hershey made his first million dollars in 1900 when he sold his Lancaster operation. He purchased 200 acres of land in Derry Township, located in Dauphin County, where he built what would become the world’s largest chocolate plant between 1903 and 1905. He developed his own special formula for his chocolate and used milk from the surrounding local dairies. His first Hershey Bar was produced in 1900, Hershey Kisses made their appearance in 1907, and the Hershey Bar with Almonds was introduced in 1908.

In 1898, Milton Hershey married Catherine Elizabeth “Kitty” Sweeney, described in newspapers of the time as a beautiful Irish Catholic woman from New York. The marriage was a happy one, but the Hersheys were disappointed to find that they could not have children. Together, they decided to become benefactors of children in need, and in 1909, they established the Hershey Industrial School for orphaned boys. These students lived along or near the trolley line and rode the streetcars to the school. To celebrate 25 years of the trust, a Junior-Senior High School was built in 1934 along the trolley line on Pat’s Hill.

A few years into their marriage, Kitty began to develop symptoms of an illness that would eventually paralyze her. She died in 1915. In 1918, Hershey donated the majority of his fortune, including control of the company, to the Milton Hershey School Trust Fund and ensured that both male and female students would benefit. He never remarried.

As the Hershey Company thrived, Milton Hershey directed the development of a town with nice homes, a trolley system, a department store, telephone and electric service, and parks and recreational facilities such as Hershey Park. Hershey always felt that he had a responsibility to his town and his employees, and that their welfare was intertwined with his company. An entire third of the town was devoted to park space, and travel to Hershey increased constantly as the town grew.

Hershey embarked on a building campaign during the Great Depression that included the famous Hotel Hershey atop a hill 200 feet higher than the surrounding area. After the Depression, he could be proud that none of his workers lost their jobs; in fact, he had hired 600 people.

During WWII, Hershey developed a chocolate bar loaded with extra calories and vitamins that could be used by the military as an emergency ration and did not melt. This was the Field Ration D bar, which was designed to withstand high temperatures, was high in food energy value, and tasted just a little better than a boiled potato. The army did not want it to taste good as it was considered an emergency ration to be eaten only when on the verge of starvation.

Later, Hershey developed the Tropical Chocolate Bar which intentionally tasted better. Over 3,000,000 of these were produced and distributed to the military throughout the world. The United States Government gave him a special award for his contributions to the war effort. Hershey died on October 13, 1945 at the age of 88. The trolley system he created outlasted him by a little over a year.

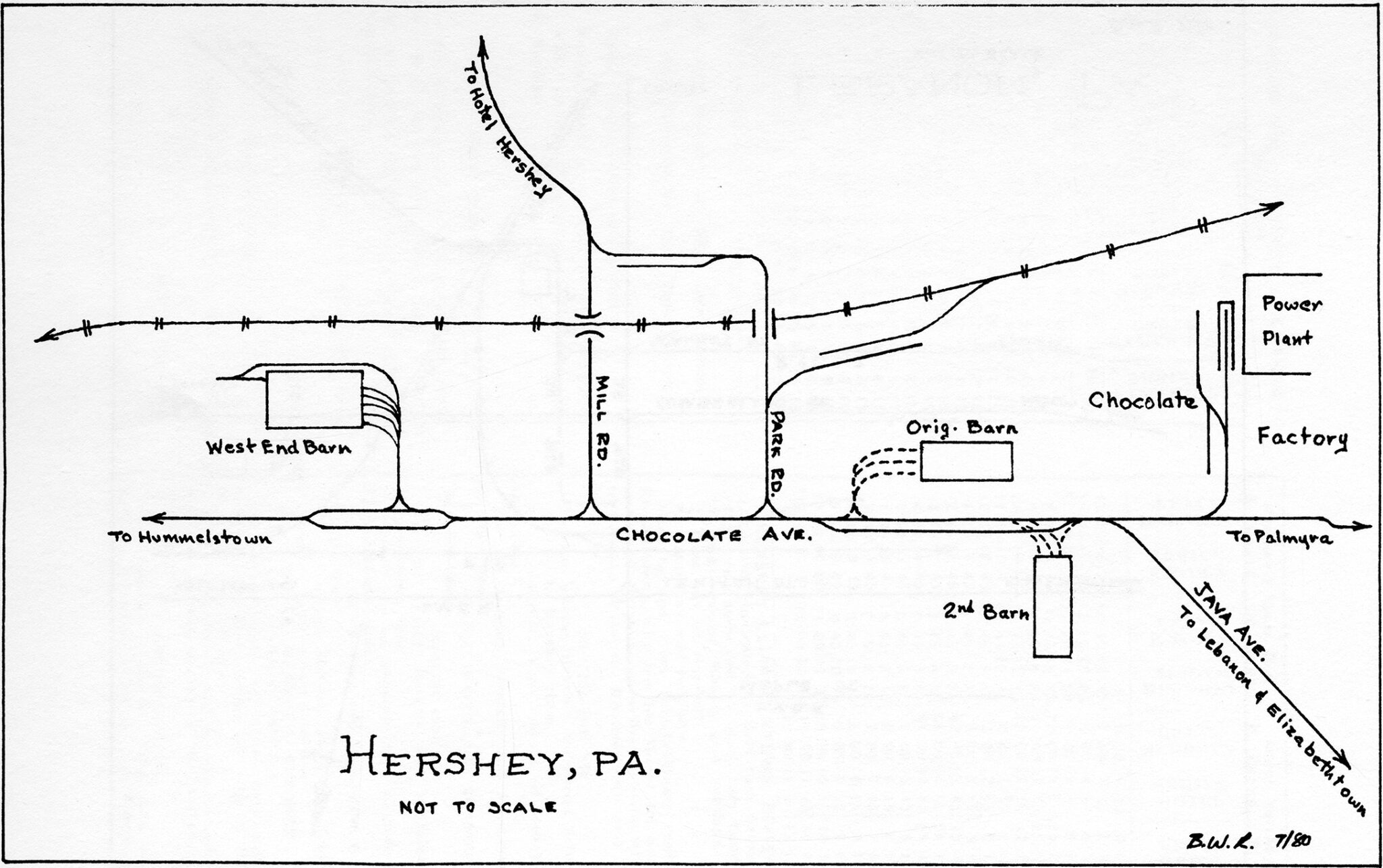

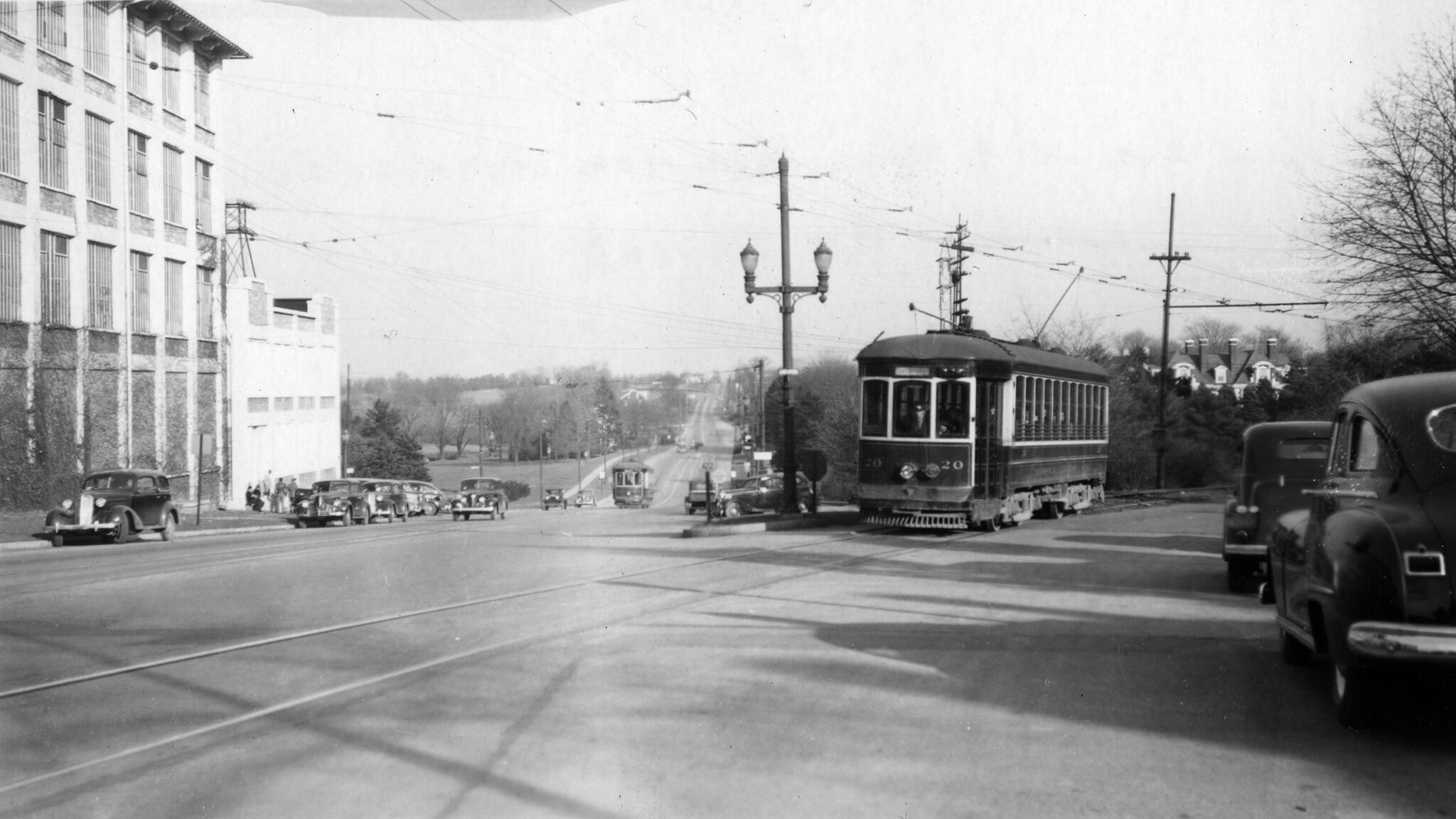

Trolleys to Chocolate Town

Milton Hershey established his factory along the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad which provided good access to carloads of sugar and cocoa beans from port cities on the East coast and would allow him to ship his finished product out. The key ingredient to the business, though, was milk. With an abundance of nearby dairies but a lack of adequate roads, Hershey sponsored and planned a streetcar system to economically transport both factory workers and the huge quantities of milk required to make chocolate to the plant. Much of the system would be built on private right of way and was carefully designed to bring residents and tourists to all the amenities the town would eventually offer.

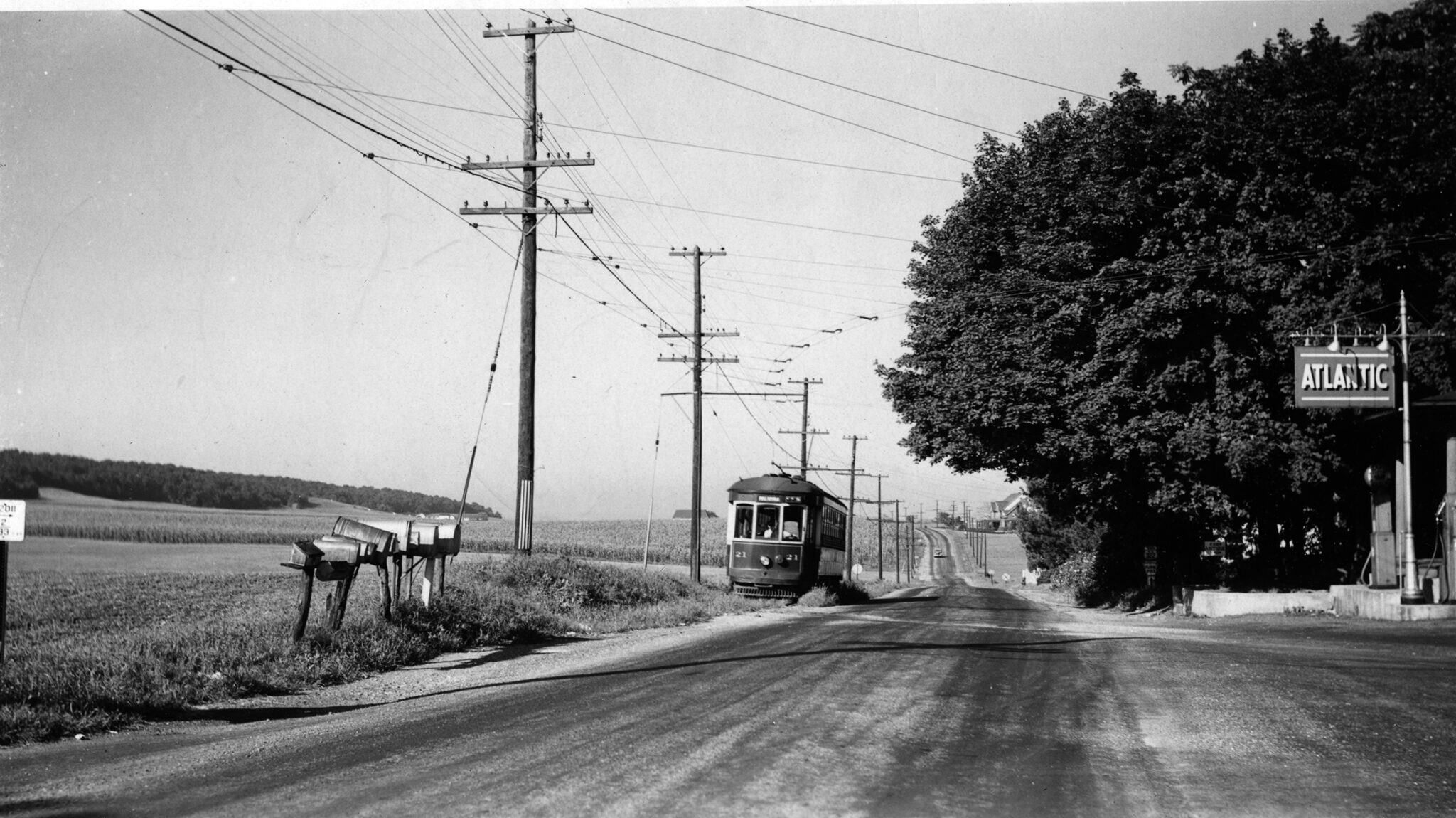

The first part of his system, chartered as the Hummelstown & Campbellstown Street Railway in 1903 to build a street railway from Hummelstown through Derry Church to Palmyra and Campbelltown, opened on October 15, 1904 when the line from Derry Church, home of the Hershey factory, began running 2 miles west to Hummelstown on a 90-minute headway. The power was furnished by the Hershey Chocolate Company, and service began modestly with 3 cars built by the J.G. Brill Company in Philadelphia. For more than forty years, streetcars served the residents of Hershey, Pa.

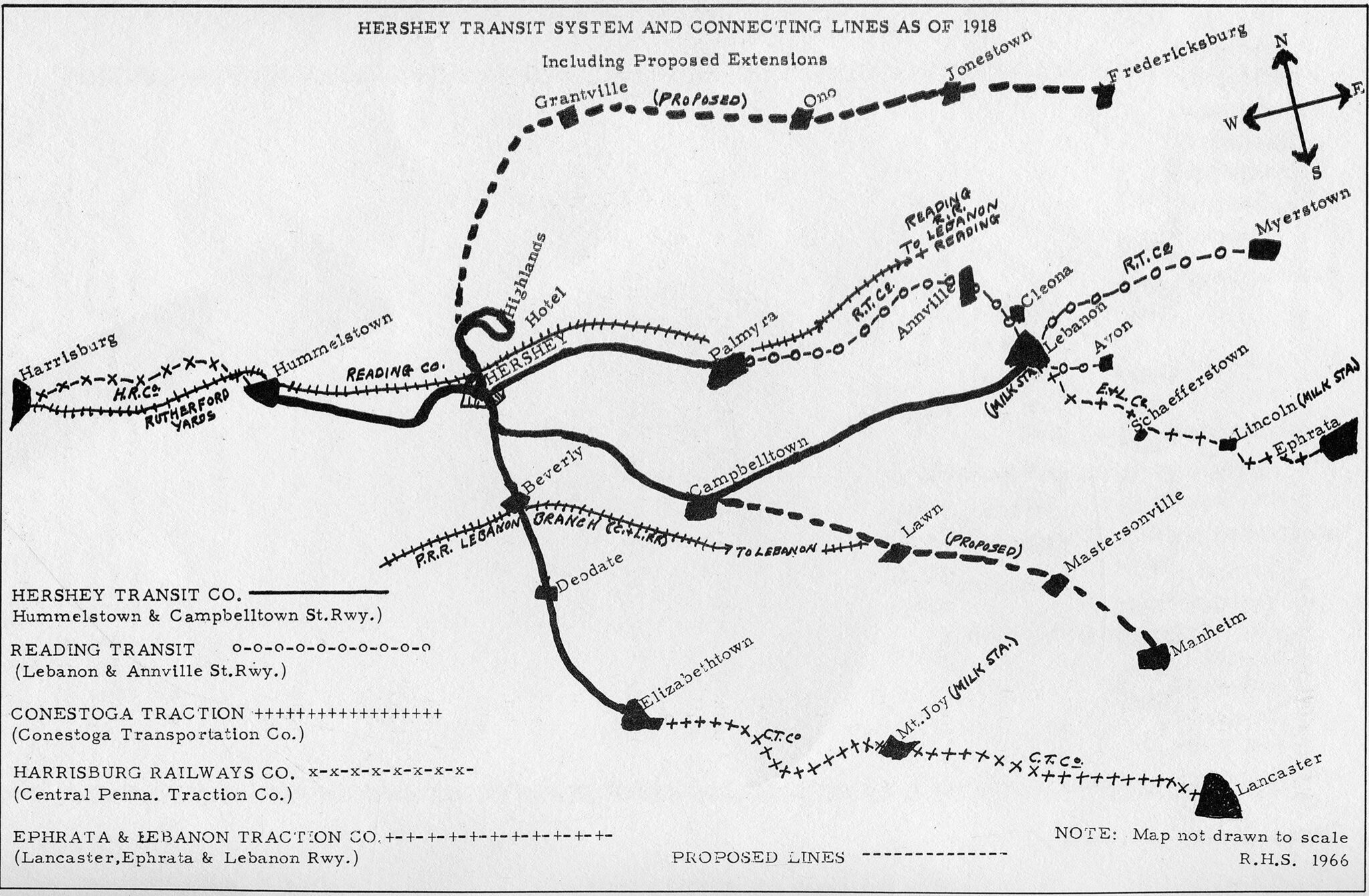

The following years were marked by expansions of the streetcar lines into the surrounding farmland and connections to lines in nearby towns. In 1905, the Central Pennsylvania Traction Company extended its Harrisburg-Rutherford line east into Hummelstown, offering Hershey residents a connection via transfer west to the state capital. About the time the Hummelstown line was opened, Hershey extended the line east 3 miles to Palmyra, where a connection was made with the Lebanon & Annville cars running to Lebanon in May 1905. The next line to be built, which branched off the main line right in front of the candy factory, went south to Campbelltown, arriving at that town in January 1908. In 1907, an extension was made from the Campbelltown line further south to the town square of Elizabethtown. Here, a connection was made with the Conestoga Traction cars coming northeast from Lancaster beginning on December 1, 1915. In 1913, Hershey milk cars would operate south over the Conestoga Traction’s rails to reach a milk station in Mt. Joy, Pennsylvania.

In 1912, the Campbelltown line was further extended east over the newly formed Lebanon & Campbelltown to reach Lebanon and connections not only with the Lebanon & Annville lines but also with the Ephrata & Lebanon Street Railway, which offered a way to reach additional milk-producing areas. The E&L originally used battery powered streetcars which could not climb the steep grade leading from Lebanon into Lincoln. After the line was electrified, Hershey sent his cars to the milk depot there, allowing him a substantial expansion into new milksheds without the expense of building his own line into Lincoln.

In 1913, expansion of the Hershey trolley system was essentially complete. Corporate matters were then tidied up with the formation of the Hershey Transit System, which absorbed the original Hummelstown & Campbellstown Street Railway and several dummy companies that had been established to pursue the additional construction to Palmyra, Elizabethtown, and Lebanon. Per a 1922 article in the International Confectioner, “the development of the transit system of Hershey is equally as interesting and impressive as the town itself. Every attention was given to establishing and maintaining a reputation for comfort, easy riding, prompt and efficient service.” Residents could take the trolley to Lancaster, Harrisburg, and even Philadelphia. The Hershey system itself consisted of about 36 miles of track at its peak.

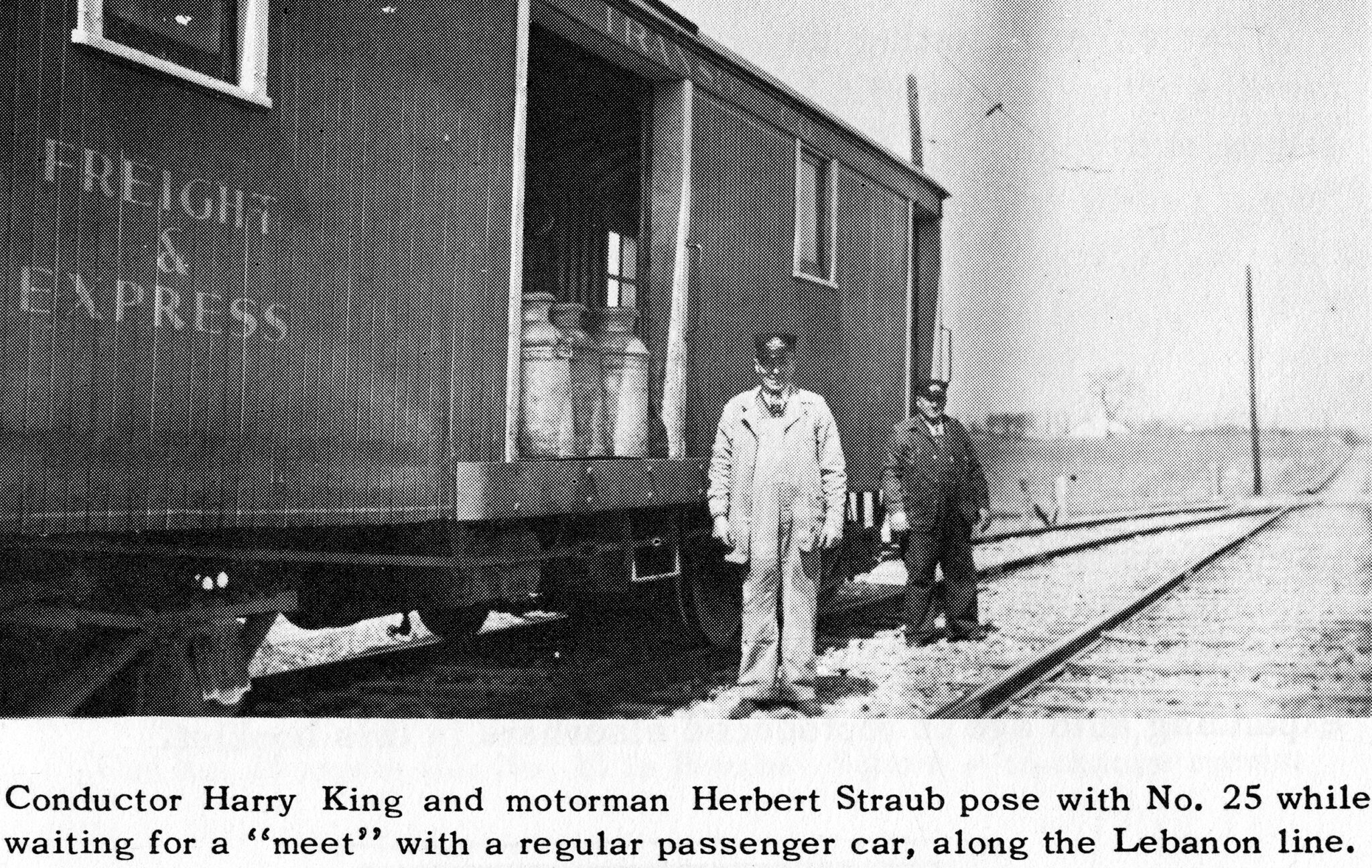

Between 1907 and 1912, the system (and chocolate company) had grown such that the “combine” cars that carried both passengers and milk freight did not have enough space for either riders or hauling milk cans. It was not unusual for a car to return from their route with 200 to 250 cans of milk aboard. The company enlarged and improved its car fleet and its carrying capacity by purchasing second-hand cars that were larger and longer plus a small order of new cars. Two new double-truck arch-roofed cars that would characteristically identify the system were purchased in 1912 from the J. G. Brill Company of Philadelphia and were so successful that additional cars of this type were bought through 1920.

Trolleys from other lines could often be spotted on the town’s streets when cars from Lancaster and Harrisburg ran over Hershey Transit rails to take picnickers and amusement park-goers to Hershey Park, especially in the summer. The traction company profited considerably from these trips.

The grand Hotel Hershey designed by Hershey and his chief engineer opened on May 23, 1933 atop a hill overlooking the community. A dilapidated trolley line that had previously looped Pat’s Hill and its reservoirs was rehabilitated to serve the “Queen of the Hill.” Initially, trolleys hauled the construction materials used for building the hotel up a steep grade; later the elegant Birney car Springfield, purchased from the street railway in Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1935, carried passengers along the picaresque section of the line to the summit. In addition to hotel guests, the route also served many schoolchildren who attended the Junior-Senior High School just downhill from the Hotel Hershey. Dedicated hotel service ended in 1940 when the Hotel Line was combined with the Campbelltown trips. Dwarfed by its larger sisters and unable to keep the schedules on the longer lines, the little Birney car was sold to the street railway in Marion, Indiana.

In its early days, the traction company’s principal source of revenue was milk from the surrounding farms supplemented by chocolate factory workers, school children going to and from the Hershey School, and charter trips by other trolley companies bound for Hershey Park. By the early 1920s, the factory consumed about 15,000,000 gallons of milk annually, much of that still hauled by trolley both from independent and company-owned dairies. However, the decade also saw enormous state and local paving and road improvement projects as dirt roadways gave way to widened macadam thoroughfares. As truck technology and capacity advanced, more and more of these vehicles were purchased by the Hershey company as well as by local farmers and dairies who then brought their milk directly to the chocolate plant. By the late 1920s, milk traffic carried by trolley began to fall off.

This situation was exacerbated in 1929 when Hershey Transit cancelled its milk hauling contract with the Ephrata & Lebanon Street Railway and ceased carrying milk via trolley from the off-line Lincoln depot. Company trucks were substituted to take the milk directly from the depot to the factory, and this move, in effect, killed most of the line’s business. It was truncated to Lebanon in 1931. That left the line to Elizabethtown as Hershey Transit’s last off-line milk and express operation, which required the use of the tracks of Conestoga Traction from the square through and beyond Elizabethtown to reach the Mt. Joy milk station. In 1932, the Elizabethtown city fathers decided to pave the city’s main thoroughfare, Market Street. With its line from Mt. Joy to Elizabethtown in terrible shape and unable to afford its share of street paving, Conestoga Traction decided to convert its entire Elizabethtown railway line to bus operation. With its rail connection to the Mt. Joy milk depot severed, Hershey Transit saw no reason to rebuild its own tracks to the square of that town and ended its service on private right-of-way at the north edge of town. Conestoga Traction conveniently extended its new bus service north to provide a connection for passengers. The loss of the Mt. Joy milk traffic had a major impact on the trolley milk operation, but the insulated express motors would continue to carry diminishing amounts of milk until 1942. After that, the chocolate plant would receive all of its milk shipments via tanker truck.

Through the 1930s Milton Hershey shielded his trolley system from losses, which amounted to about $9,000 annually, through his more profitable ventures. However, as the 1940s dawned, it appeared that all streetcar operation would soon come to an end. The Elizabethtown line was abandoned in June of 1940 followed by the Lebanon line being cut back to Campbelltown in January of 1942. Trolley service would quite probably have disappeared by 1942, but WWII intervened, and the Federal Government ordered the remaining trolleys to operate for the duration of the war. It all finally ended on December 21, 1946, when the Hummelstown – Campbelltown line was taken over by a Reading Street Railway subsidiary, the Hershey Coach Company, to provided service by bus between Palmyra and Hummelstown. The Hotel line was abandoned outright with no replacement service.

Museum members Fred W. Schneider and Ed Lybarger both indicate that Hershey is not listed as an official Pennsylvania town. Hershey was developed as a company town but still remains as an unincorporated community within Derry Township. Today, two Hershey Transit trolleys survive under cover at the historic West Car Barn, preserved by the Friends of the Hershey Trolley.