Larissa Gula

In 1986, Presidential Proclamation 5443 designated February as National Black History Month. “Black history is a book rich with the American experience but with many pages yet unexplored,” President Reagan said in this Proclamation. He also stated, “The foremost purpose of Black History Month is to make all Americans aware of this struggle for freedom and equal opportunity.”

This struggle can be seen in many aspects of history, including in transit. At the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum, our exhibits explain to visitors how important streetcars were to growing cities and the people who lived in them. Sadly, post-Civil War, freedom from slavery did not mean equality. This is especially evident when reflecting on the stories and events that took place aboard public transit.

Segregation and discrimination were the norm on public transit for much of American history. This Black History Month, we’re remembering some of the historical figures who fought against these inequalities, as well as the significant events and protests that resulted from these efforts.

New York, 1854

Elizabeth Jennings Graham

Portrait of Elizabeth Jennings Graham in “The Story of an Old Wrong,” The American Woman’s Journal, July 1895. Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka, Kansas.

Elizabeth Jennings Graham was an African-American teacher and civil rights activist. Today she’s known as “The Rosa Parks of the 19th Century”.

In July 1854, the 24-year-old woman boarded a Third Avenue Railroad Company horsecar in lower Manhattan. She and a friend (Sarah Adams) were traveling to the First Colored American Congregational Church. Together they tried to board a white-only car.

They were ordered off of the car and told to board one that served African American passengers. Elizabeth ignored the order because the second car was too full to board. In her recounting of the event, she said she told the conductor: “I was a respectable person, born and raised in New York, did not know where he was born and that he was a good for nothing impudent fellow for insulting decent persons while on their way to church.”

Sarah was quickly removed from the horsecar, and the driver and conductor attempted to remove Elizabeth as well. When she resisted their efforts, she was forcibly (and violently) removed by police. She wrote a letter recounting her forcible removal, which was read in church the next day. Her letter was then forwarded to The New York Daily Tribune (whose editor was the abolitionist Horace Greeley) and to Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Both papers reprinted the letter.

Something important to know about Elizabeth is that she was born free in New York City to Thomas and Elizabeth Jennings. Her parents were both members of New York City’s small African-American middle class. This meant that, unlike many African American riders, Elizabeth was a person with resources at her disposal.

After the incident, Elizabeth used her resources to sue the driver, the conductor, and the Third Avenue Railway. (She was represented by then 24-year-old Chester Arthur, who went on to become America’s 21st President.) At the time, segregation was not the law in New York City; it was instead a cultural norm. This allowed Judge Rockwell of the Brooklyn Circuit Court to rule that: “Colored persons if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the same rights as others and could neither be excluded by the rules of the company, nor by force or violence.”

On March 2, 1855, Douglass’ Paper reported that Jennings would be awarded $250 in damages (less than the $500 for which she had asked).

Elizabeth’s case is the first recorded legal victory for equal rights on public transportation. Sadly, Judge Rockwell’s own ruling would be used to prevent other African American passengers from boarding public transit; specifically, transit workers began to accuse riders of being poorly behaved, drunk, or ill.

To push for further progress and equal ridership, Thomas Jennings founded the Legal Rights Association to challenge transit companies that continued to run segregated services. By the end of 1861, the entire New York City system had been desegregated. (It was not until 1873 that the New York State legislature passed a law that explicitly outlawed discrimination on public transportation statewide.)

Philadelphia, 1859

Segregation During the Civil War

New York City was hardly the only northern city that segregated and discriminated against African Americans. As early as 1859, African Americans were fighting against segregated transit in Philadelphia.

At the time, African American women would ride public transit to transport provisions and healthcare resources to Civil War soldiers. Black soldiers of course played an integral role in the Civil War; yet the people who traveled to support these troops were beaten and tossed from public transit if they boarded the “wrong” car.

Many women intentionally boarded segregated cars in protest. Conductors, police, and passengers alike would attack women protesting against segregation in Philadelphia. One woman who suffered in the name of civil disobedience was Caroline LeCount, a local educator and activist.

We know that one elderly African American woman eventually successfully sued a conductor for injuring her when he threw her off a car in 1865. That woman was coming from a church where she was helping wounded African American soldiers.

Not every member of the African American thought the protests were productive. William Still, a local Black activist and businessman (who was also helping to run the Underground Railroad) preferred to write letters to state and local officials. Still wrote that discrimination and segregation were ultimately hurting the Union cause.

Still also worked with Stephen Smith, Isaiah Wears and Jonathan Gibbs – members of the Social, Civil, and Statistical Association of the Colored People of Pennsylvania – to write the Petition For The Colored People Of Philadelphia To Ride In The Cars in 1862. The petition was directed to the managers of the city’s passenger cars, and stated that the prevention of Black people from riding public transit was an inconvenience.

Ultimately these petitions and letters yielded no significant change. Instead, segregation aboard public transit in Philadelphia ended following a major campaign in the 1860s. Regular protests were organized by the Union League of Philadelphia to denounce the forcible ejection of several African American women from public transit.

Then on May 17, 1865, Octavius Catto – a member of the Union League – boarded a white-only passenger car. It’s reported that the conductor of the car ran it off the tracks, detached the horses that were pulling it, and left Catto. The man remained in the car, and his sit-in eventually attracted a crowd. Newspapers covered his protest, including The New York Times.

Over time, the pressure created by the Union League’s ongoing protests (as well as the publicity of the protests) contributed to the passage of a new bill in 1867; it by law prohibited segregation on transit systems in the state of Pennsylvania.

African American scholar Dr. W.E.B. DuBois wrote about this struggle in his 1899 book “The Philadelphia Negro”. He reflected on the 1867 law: “After public meetings, pamphlets and repeated agitation…[Blacks] gained what decency and common sense had long refused.”

New Orleans, 1867

William Nichols and the New Orleans Streetcar Protests

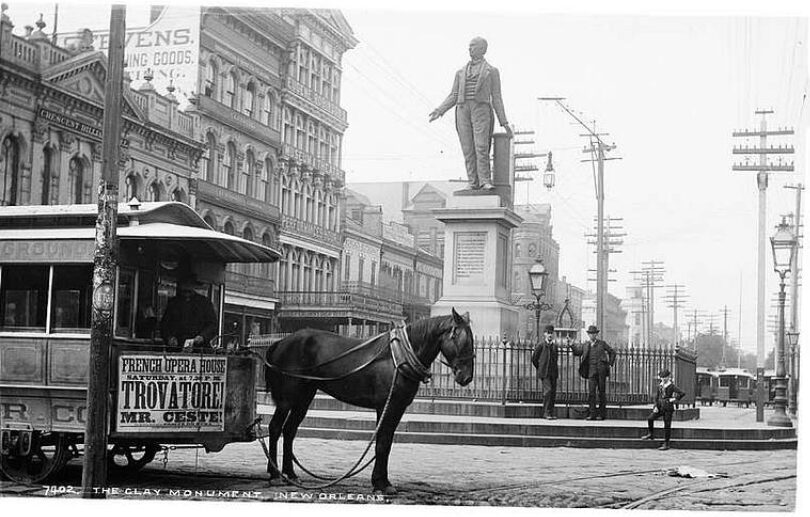

The Clay Monument, Canal Street, New Orleans – photo no. 8102 W. H. Jackson Views (1898). Detroit Publishing Co. no. 7402. State Historical Society of Colorado; 1949.

As efforts against segregation moved forward in the North, Black leadership also organized in the South. Post-Civil War, the state of Louiosiana was home to a large, educated, and prosperous free African American population that was ready to move against segregation. Their efforts were also supported and publicized by the writings of the New Orleans Tribune – the first Black-run daily newspaper in the United States.

On April 28, 1867 (two years after the end of the Civil War), William Nichols boarded a ‘white-only’ horsecar in New Orleans. Some sources report that he did so with the support of two white allies; others say he did so alone. Ultimately, he was forced to exit the car by its driver. Police then arrested Nichols for disturbing the peace by entering a car “set apart for the exclusive right of white persons.”

When Nichols went to trial, the judge dismissed all charges against him, specifically to avoid creating a precedent by giving a definitive ruling in the case. Nichols immediately countersued the streetcar driver for assault. In response, to prevent other lawsuits, the transit company issued new orders to its drivers: instead of forcibly removing African Americans who boarded “whites-only” cars, they should refuse to drive until African American passengers disembarked.

In the following weeks, thousands of African Americans engaged in citywide protests against the policy. It’s reported that crowds of protesters “swamped” white-only cars, bringing transit service to a halt. And at one point, 500 people even assembled in front of Congo Square and watched protestors drive commandeered cars back and forth on the tracks.

Fearing the growing risk of violence, the chief of police ordered the desegregation of the city’s horsecars. This decision marks one of the few times when protests in this era led to a successful outcome. New Orleans’ transit system remained integrated until 1902 – when, in the wake of the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling of 1896, mandated segregation became law in the city once again.

1900 to 1907

Post Plessy v. Ferguson

The Charles L. Franck Studio Collection at The Historic New Orleans Collection

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) was a Supreme Court ruling that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution, as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality. The ruling made it easier for states to enshrine segregation into law. (It’s worth noting that if Plessy v. Ferguson had been ruled back in the 1850s, Elizabeth Jennings might not have been able to take the legal action that she did.)

The laws didn’t stop communities from organizing against segregation. Between 1900 and 1907, African Americans in twenty-five Southern cities organized protests against laws that declared public transit could be “separate but equal.” Examples of the cities that fought against the laws include Little Rock, New Orleans, Richmond, and Savannah.

Each community organized in its own way. In Richmond, the African American community used newspapers to organize a boycott of the city’s streetcars. They would walk to work or find alternative means to get to work (a tactic later adopted by the activists of the 1950s).

It’s worth noting that initially, Virginia law did not require segregation. However, the Virginia General Assembly altered its legislation in 1906. Segregation became mandatory aboard public transportation. The boycott lost steam not long after this decision.

Richmond’s story is just one example of how resistance against segregation laws were not successful at this time. The reasons varied from city to city. In some cases the movements lost momentum due to issues with local leadership; in other instances, additional laws were implemented that actually made it illegal to boycott or picket a “lawful business.”

Some laws went even further, and forbade the “publishing or declaring that a boycott…exists or has existed or is contemplated.” If the Richmond boycott had not already lost its momentum, such a law would surely have hampered local activists’ efforts.

1908 Onwards

The Impact of the Automobile

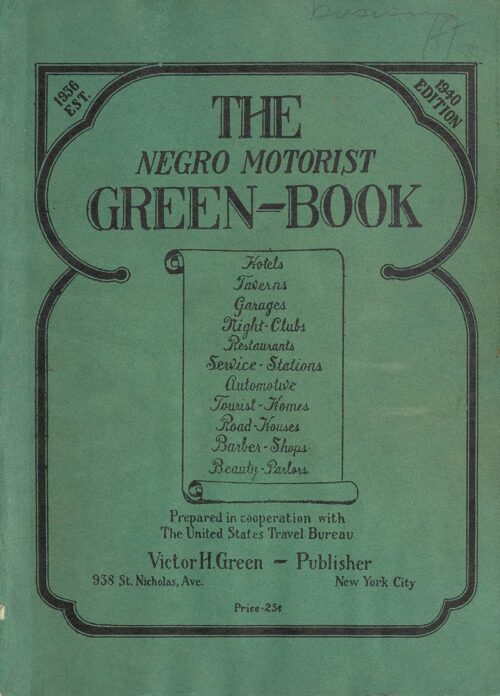

The Negro Motorist Green-Book (1940 edition) – Scan of cover (New York Public Library copy)

At a time when the law denied African Americans equality aboard public transit – and even suppressed efforts to protest the injustice – the introduction and growing accessibility of the automobile was significant. The automobile was, as we know, a thorn in the side of public transit. Automobiles offered convenience and mobility to all drivers; but they especially symbolized freedom to African Americans.

“Jim Crow” laws and policies limited African Americans’ access to transit, which directly affected their quality of life. Travel by car became a way of resisting the everyday racial discrimination experienced aboard buses, trolleys, and trains. Instead of organizing against streetcar companies, African Americans began to take actions that helped them to benefit from automobile ownership and travel.

Access to and traveling via car presented their own challenges, of course. Assuming a Black family could afford an automobile or had a way of borrowing one, traveling by car didn’t end discriminatory laws or eliminate the dangers associated with passing through primarily white communities – especially in sunset towns.

By 1936, Victor Hugo Green began publishing “The Green Book” – an annual guide of stores, hotels, gas stations, and restaurants that welcomed African Americans. The history of The Green Book is fascinating in and of itself. The creation of the guide symbolizes that African Americans knew it would take time to fight against segregation. And so rather than wait for the equal right to ride aboard public transit – which wasn’t granted until the 1960s – African American communities found other ways to travel in America.

Philadelphia, 1944

The Philadelphia Transit Strike

First African American trained by P.T.C., July 31, 1944. Courtesy of the Special Collections Research Center. Temple University Libraries. Philadelphia, PA.

Many moments in Black transit history involve efforts to desegregate horsecars, streetcars, and buses. But as one infamous incident shows, there were also struggles over transit company hiring policies throughout history.

In 1944, the Philadelphia Transportation Company (PTC) decided to allow its minority employees to hold non-menial jobs, such as motormen and conductor. These jobs were previously reserved for white workers only – but at the time, there was a labor shortage due to the company’s white employees being called to serve in World War II.

A total of 1,200 PTC employees were serving in the armed forces. To combat this shortage in staff, the company initially campaigned to hire women. By the end of 1943, the company had recruited over 300 female operators. Another 800 worked in the PTC’s shop, maintenance, and clerical units.

The PTC’s management and white workforce alike had, to date, fostered a hostile and racist culture on the company’s property and in its shops. It had been well known that African Americans had “no hope” of working as motormen, conductors, or drivers at PTC.

Then in 1944, it was announced that eight African American men were hired as streetcar motormen or conductors. White transit employees went on strike on August 1st, and refused to work with these new hires.

The strike brought transit in Philadelphia to a halt for several days. Without transit, the city came to a standstill – which in turn crippled its war production. And so, the strike’s impact on the military’s needs led to government involvement. On August 3, 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to take control of the PTC. Major-General Philip Hayes was put in charge of the PTC’s operations.

After determining that the strike leaders could not be negotiated with, Hayes issued an order that the striking workers return to work on August 7, 1944. Per the order, those refusing to comply would face a range of consequences based on their age. Those between the age of 18 and 35 would be sent to the Army. All others would be fired, stripped of their military draft deferment, and denied job availability certificates by the War Manpower Commission for the duration of the war.

The ultimatum worked; the strike ended and the white workers returned to work. (It’s said that work attendance at the PTC was never higher than on August 7th.) An armed soldier was also posted on every streetcar, bus, subway, and El car. These troops stayed in Philadelphia until the 17th, at which point training had ended for the African American hires.

Reflecting on Public Transit in Black History Month

(and Beyond)

History makes it clear that public transportation was a pivotal space for civil rights activism. As these recountings show, there are many names in history worth remembering in the fight for equality aboard public transit.

Believe it or not, there were more names and stories we could have shared in this write-up! If this has been interesting to you, and you’d like to continue learning about Black history in transit, we recommend continuing with the following articles and resources:

-

- Article: Cincinnati Public Radio’s education outeach project has an excellent writeup about Sarah Mayrant Fossett, who also protested streetcar segregation (as well as served on the Ungerground Railroad).

- Article: The Zinn Education Project has many articles on this topic, including one about Charlotte Brown of San Francisco.

- Article: The Market Street Railway has a wonderful article about the various individuals who helped break racial barriers in San Francisco transit.

- Book: “Running the Rails: Capital and Labor in the Philadelphia Transit Industry” is a book by James Wolfinger. The author explores the history of Philadelphia’s sprawling public transportation system – and also explores how labor relations (including racially motivated policies and programs) shifted from the 1880s to the 1960s.

- More Books: Last year, staff and volunteers shared our favorite books about Black American transit history. If you didn’t check them out in 2023, we recommend doing so in 2024!

- Trolleyology Talks: Finally, interested viewers might enjoy hearing more about Black history in our Trolleyology talks. We invite you to watch “Jim Crow Streetcars” or “On the Warpath” on our YouTube channel.