Larissa Gula

What do you think of when imagining a fun summer day? Perhaps you picture a picnic in a scenic setting. Perhaps you picture a day at an amusement park. If either of these outings came to mind, you might be interested to know that your favorite summer activities have a direct connection to transit history.

100 years ago, you would have boarded a streetcar to travel to your favorite picnic site or amusement park. Not only that: the amusement park was likely owned and operated by the very transit company providing you with transportation. These destinations were known as trolley parks, and during summers past, Americans flocked to thousands of these sites for a day of fun.

This postcard shows theatergoers boarding trolley cars for the trip home after a show at Riverton Park in Portland. Source: New England Electric Railways History Society

How Trolley Parks Got Their Start

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, streetcar companies were starting to reshape cities and neighborhoods alike. Prior to the introduction of the streetcar, American cities were built first and foremost as walking cities, meaning that most residents worked and shopped close to where they lived.

Streetcars made it possible for riders to venture further than they could on foot, and were a faster and cleaner option than horse-drawn transport. Of course, people who were used to living in walking cities would have already built their life and routine based on, well, what they could walk to.

The management teams of early transit companies quickly realized that they had a ridership problem due to these well-established routines. While many workers began choosing to ride the streetcar to work, they – and their families – simply did not have much of a reason to take public transit in the evenings or during the weekends. This meant streetcars were full during work hours, but were otherwise empty.

To solve this ridership issue, a number of transit companies decided to build attractions to encourage people to ride streetcars outside of work hours. These attractions are what we now remember as trolley parks.

The average trolley park began as a picnic grove. Families would ride streetcars to a beautiful area – which was often built near a lake or river – and enjoy the green spaces and picnic shelters set up within a park. As the groves became more popular, transit companies began building additions to entertain new and repeat riders alike. These additions were initially simple attractions, including dance pavilions and concession stands. They weren’t tremendous by today’s standards, but they made already popular parks and groves even more pleasant to be in.

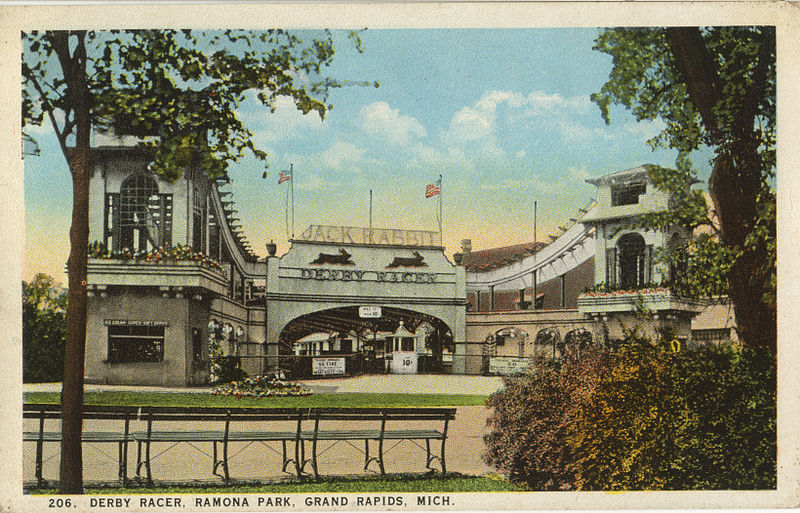

This postcard features the Derby Racerat at Ramona Park in Grand Rapids, MI. Source: East Grand Rapids MI History Room

From Picnic Groves to Amusement Parks

The popularity of trolley parks continued to grow, so much so that the simple attractions evolved into larger attractions. Previously simple picnic grounds often began including carousels, Ferris wheels, and live music and entertainment. The waterways that once offered a beautiful backdrop became attractions where visitors could go swimming or take a boat ride. In the winter, these same waterways often became ice skating rinks.

It didn’t stop there. Soon, the growing attractions transformed the former picnic groves into our traditional idea of an amusement park. Expanding parks added thrilling rides such as aerial swings, bumper cars, and roller coasters. Swimming pools were built in some parks, particularly in cases where lakes or waterways could no longer accommodate both boaters and swimmers. And a mixture of game stands, indoor theaters, and outdoor performance spaces made it possible for guests to access more entertainment than ever.

As trolley parks evolved past their picnic grove roots, they remained popular with families. But families weren’t the only riders enjoying the thrills of these evolving parks. Transit companies would happily shuttle organizations to group picnics at these parks as well. Churches, schools, unions, businesses, social clubs, and any other group you can think of all would have used the streetcar to travel to their group outings.

By 1919, there were an estimated 1,000 amusement parks around the country, and most of them were trolley parks – meaning that they were founded by, and were often still owned by, a transit company. Pittsburgh alone had nearly two-dozen such trolley parks between the late 1800’s and mid 1950’s.

The Jack Rabbit coaster at Kennywood, outside Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, debuted in 1920 and continues to thrill passengers today. The trolley park opened in 1898. Source: Palace Entertainment

The Decline of the Trolley Park

The 1920s are now remembered as the golden years of trolley parks. Sadly, their decline is a story we know all too well at the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum, as it directly connects to the decline of the streetcar itself.

Henry Ford envisioned making automobiles for all Americans, and unveiled his first Model T as early as 1908. Within eight years, after developing and fine-tuning an assembly line mode of production, Ford was able to decrease the cost of his Model T from $825 to $345.

Ford’s assembly line is credited with raising the standard of living for American families and contributing to the rise of the American consumer economy after World War I. And a consequence of this shift, as a Smithsonian exhibition puts it, was that, “Cars became the commuter option of choice for the growing number of people who could them.”

Automobiles impacted trolley parks in two key ways. Firstly, they directly affected ridership as more people chose not to ride on streetcars to visit a trolley park. And should someone choose to drive to a trolley park, they often found that there was nowhere to park their vehicle. This meant that transit companies saw a decline in both passengers and visitors, which created a financial strain and made the majority of trolley parks unprofitable.

Already facing declines in business, many trolley parks’ fates were sealed with the arrival of the Great Depression. Already declining ridership plummeted dramatically, and struggling streetcar companies could no longer afford to maintain or power the parks.

The Legacy of Trolley Parks

Trolley parks as the nation once knew them are now all a 100-year-old memory. However, you might be interested to know that eleven amusement parks today got their start as historic trolley parks. They are:

- Camden Park in Huntington, WV

- Canobie Lake Park, in Salem, NH

- Clementon Park in Clementon, NJ

- Dorney Park in Allentown, PA

- Kennywood in West Mifflin, PA

- Lakemont Park in Altoona, PA

- Midway State Park in Maple Springs, NY

- Oaks Amusement Park, in Portland, OR

- Quassy Amusement Park, in Middlebury, CT

- Seabreeze Amusement Park, in Rochester, NY

- Waldameer Park in Erie, PA

Note that four of these eleven operating parks are located in Pennsylvania!

In an interview with NBC News, historian Jim Futrell summarizes the significance of their survival perfectly: these parks are each a holdover from our state’s manufacturing era, when trolleys transported workers to factories and companies used the parks for annual picnics. Today, families continue to make memories at each of these wonderful parks.

Want to Learn More About Trolley Parks?

If you’re interested in learning more about the trolley parks we lost to time, we highly recommend author Jennifer Sopko’s talk on the “Lost Trolley Parks of Western PA.” Jennifer has previously shared her research with both the Pennsylvania Trolley Museum and the McKeesport Heritage Center (whose lecture is available on YouTube). Her current ongoing book project is also focused on western Pennsylvania’s lost amusement parks!